Coit Tower Murals

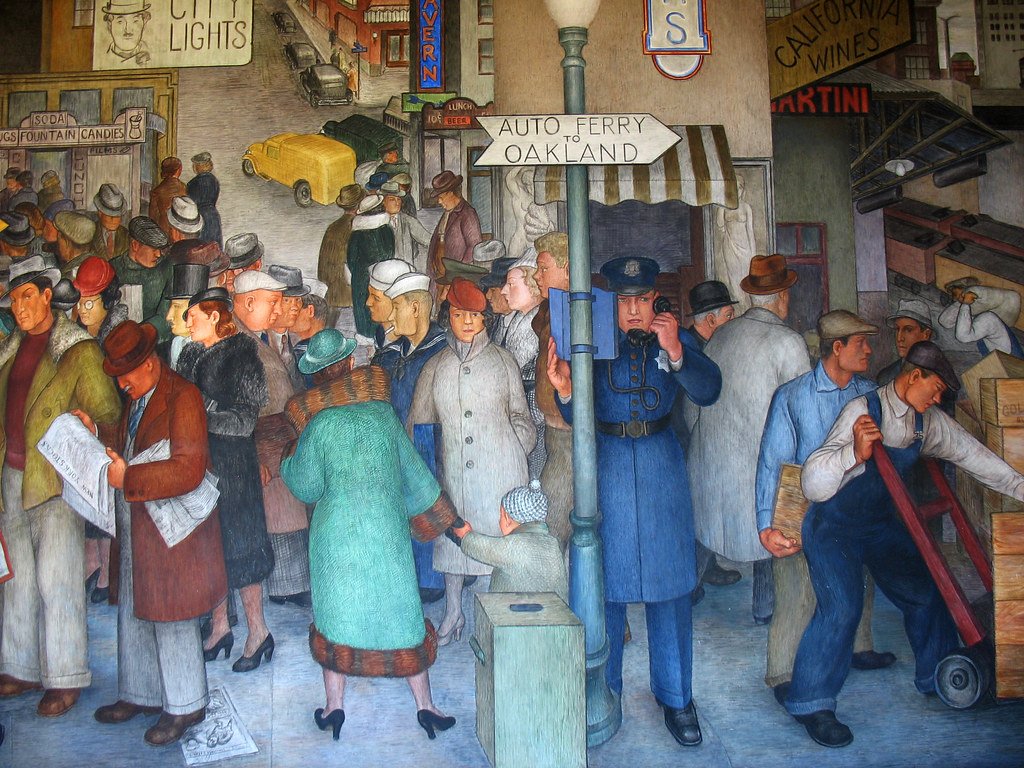

The murals adorning the interior of Coit Tower are wonders of public art. Presenting vivid and varied scenes of California life during the 1930s, they are viewed by thousands of visitors a year. When the murals were completed, they were so controversial that Coit Tower was padlocked, the windows painted over, for more than three months.

They may have been the world’s first and only fresco- driven Red Scare.

Art, Politics, and the Red Scare

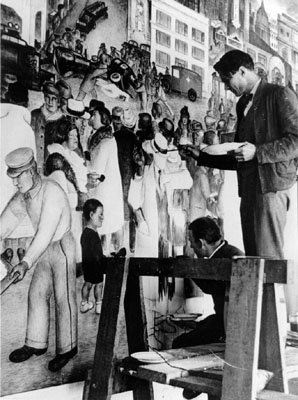

The murals were funded by the Depression-era federal program called the Public Works of Art Project, whose mission was to provide employment to thousands of American artists, while beautifying public buildings and spaces. Coit Tower’s murals were the first PWAP in the country. Eventually the project was expanded to other public buildings, like Post Offices. Many of them remain to this day.

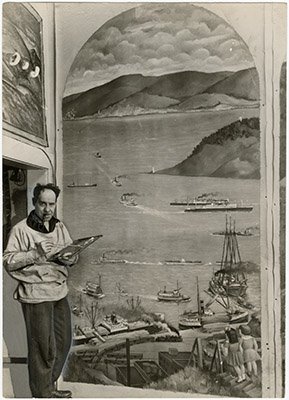

In December 1933, city officials chose 25 artists who would be paid $25 to $45 a week to create murals at the soon-to-open Coit Tower depicting “aspects of life in California.” Many of the artists admired Diego Rivera, the left-wing Mexican artist who had recently created two frescoes in San Francisco. At least four of them — Bernard Zakheim, Clifford Wight, Victor Arnautoff and John Langley Howard — were members of the Communist Party. They would be at the center of the furor that was about to erupt.

On May 9, 1934, tensions between unions representing city longshoremen and the shipping companies came to a head. The longshoremen went on strike, paralyzing the city’s economic engine. The shipping companies blamed Communist agitators, a refrain picked up by the press and local and federal officials. This red scare played a crucial role in the uproar that followed.

Controversy within Symbols

Two images ignited the controversy. First, by British artist Clifford Wight. His three small murals depicting the competing economic systems of capitalism, the New Deal and Communism. In the Communist panel, He painted a hammer and sickle, accompanied by the caption “Workers of the World Unite.” The second, was John Langley Howard’s “California Industrial Scenes” fresco, of workers beneath a banner of the communist publication Western Worker.

When officials learned about these images, they became alarmed. Herbert Fleishhacker, a conservative city banker who was the most powerful member of the committee allocating the Public Works of Art funds, ordered Coit Tower closed, whitewashing the windows, preventing anyone from seeing the murals. The official opening of July 7,1933 was canceled.

The press, smelling scandal, dove in. The San Francisco Chronicle ran a headline, “Is This Red Propaganda? Murals on Coit Shaft Hint Plot for Red Cause.” Two days later, violence erupted on the waterfront when police and strikers clashed. Two men were killed and dozens wounded becoming infamous as Bloody Thursday.

Censorship and Compromise

Confronting an increasingly fraught situation, officials in Washington decided the offending murals would be painted over. Wight refused to remove his hammer and sickle A group of ‘radical’ artists and writers picketed Coit Tower. Most of Wight’s fellow muralists did not support him: Sixteen signed a statement stating opposition to the symbol as it “has no place in the subject matter assigned.”

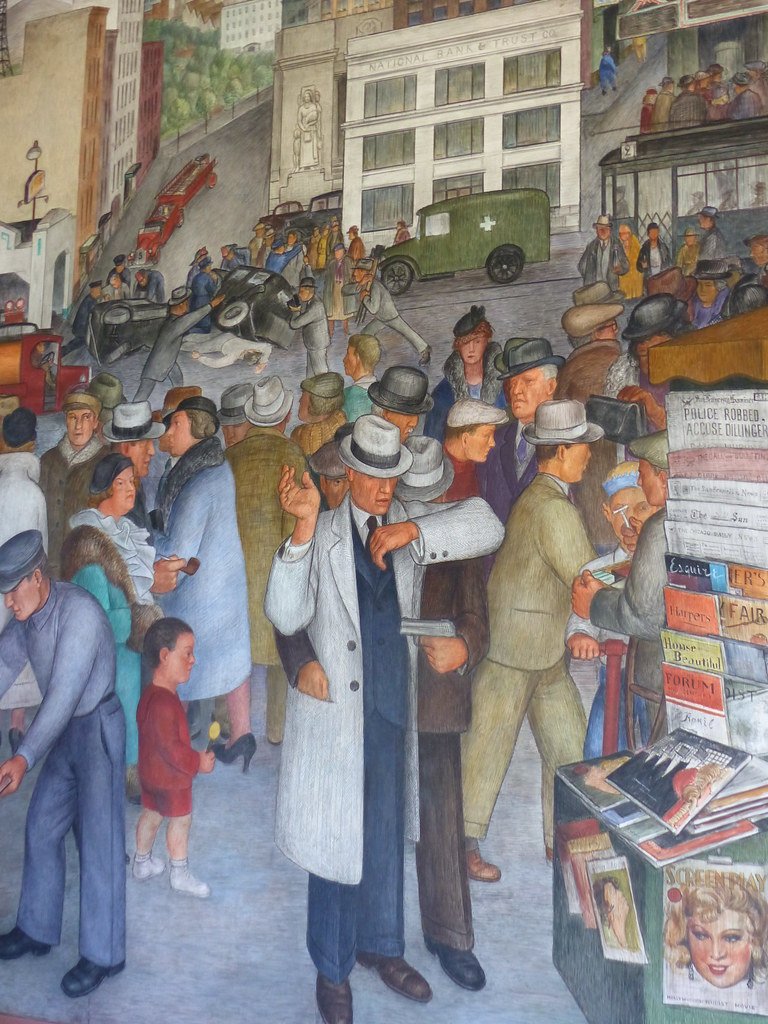

In the end, only the hammer and sickle and the Western Worker banner in Howard’s mural were covered. Victor Arnautoff’s “City Life” mural came under attack because it depicted a newsstand that did not include the conservative SF Chronicle newspaper, emerged unscathed, as did Bernard Zakheim’s “Library,” which featured a man taking down a copy of Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital.”

The Coit Tower murals, now beautifully restored, remain one of the city’s crowning artistic glories.